On Saturday I experienced total darkness. Deep-space dark. Bottom-of-the-ocean dark. The kind of dark that never brightens, because there isn’t so much as a spark for your eye to train to.

I was in a cave. There’s a network of them in Torquay, about half an hour from where I’m living: empty bellies formed beneath the earth 2.5 million years ago, by water slowly eroding the Devon limestone. I went because I wanted to feel it: the long-gone past echoing in my ribcage while I stood, sightless and suddenly strange to myself.

It felt like occupying a different body, or maybe a different world. Where space is a sound—the drip, drip of water falling from nowhere, onto nothing—and time is only the beating of your heart.

At least, it felt like that for approximately 2.5 seconds. Then the guide snapped his torch back on, roared: “How d’you like that? They don’t sell blackout blinds like that at B&Q, do they?”, and quickly flicked the switches that would light up the cavern like the Vegas strip.

***

Human culture was birthed in the deep dark. Of course, we can’t know about all the prehistoric art and place-making that’s been lost above ground; we don’t know the full extent of the rituals that made up the earliest human life. But we do know something about caves. We know beyond doubt that our oldest ancestors sought them out for much more than protection from the elements. In the echoing depths of the earth, they painted galloping horses and bison, aurochs and deer, and mysterious forms mingling humans and animals, painting them often in the cave’s most resonant hollows—places where a struck drum or a raised voice would ring out and return multiplied, like the cave itself singing back. Other times, they painted these images in narrow crawl spaces, wide enough for just one or two humans.

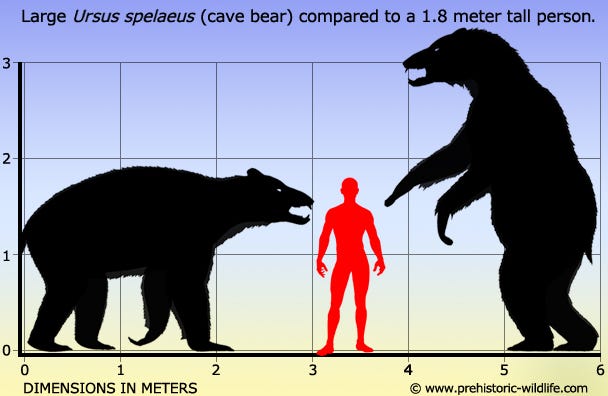

These were no galleries. Something else was going on down there, and we can never know what, but we can try to feel into it. Can you imagine? What it was like to be down where the rock starts to press in, where no light has ever reached, and where any cavern, any tunnel might hold a hyena or a cave bear? With only a lit snatch of moss soaked in animal fat to light your way. Can you even begin to dream of what might drive someone down there?

We can only ever guess, but these days, some researchers favour a shamanic interpretation. David Lewis-Williams in particular has interpreted cave art, as well as the practices of remaining indigenous cultures, to suggest that caves were shamanic sites for neolithic man. Places where a community’s edge-walkers, those whose ears and souls were tuned to the frequencies of other worlds, other dimensions, would descend to access widened states of consciousness. The paintings, it’s been suggested, are the records of these shamanic rituals.

I’m not even going to try to be impartial here: I am desperate for this to be true. Every cell in my body hums to the tune that our ancestors squeezed into the earth’s deep belly because for them—and so for us, still somewhere in these bodies—there were dimensions of experience, of the universe, and of the world’s soul that could be accessed nowhere else. And these were dimensions they had to know.

I want this to be true for the same reason that I wanted to go to the caves on Saturday, and the same reason that whenever our guide roared off to a new chamber, Pied Piper-ing the group with his torch and the reverberation of his dad jokes on the earth-old walls, I lingered in the sudden, stone-cold dark for as long as I dared, listening to the echo of my own breath. Because I feel it too. The call of those otherworlds.

So what is it that can only be accessed down there in the deep dark? And what does it have to do with going home? I’ll be offering some more thoughts on that next week.

Love,

Xx Ellie