Reading is a psychedelic drug, and medieval monks knew how to do it best

On a millennium of change in the way we read, what we've lost, and how to read to meet god on the page

Hi, friends,

I’ve written about this before—one of the most powerful mystical experiences of my life.

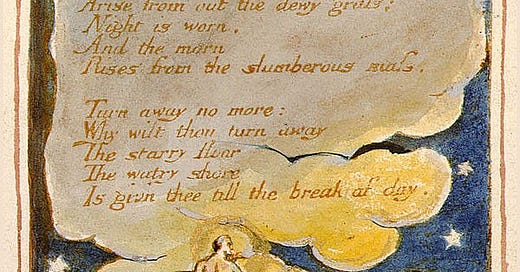

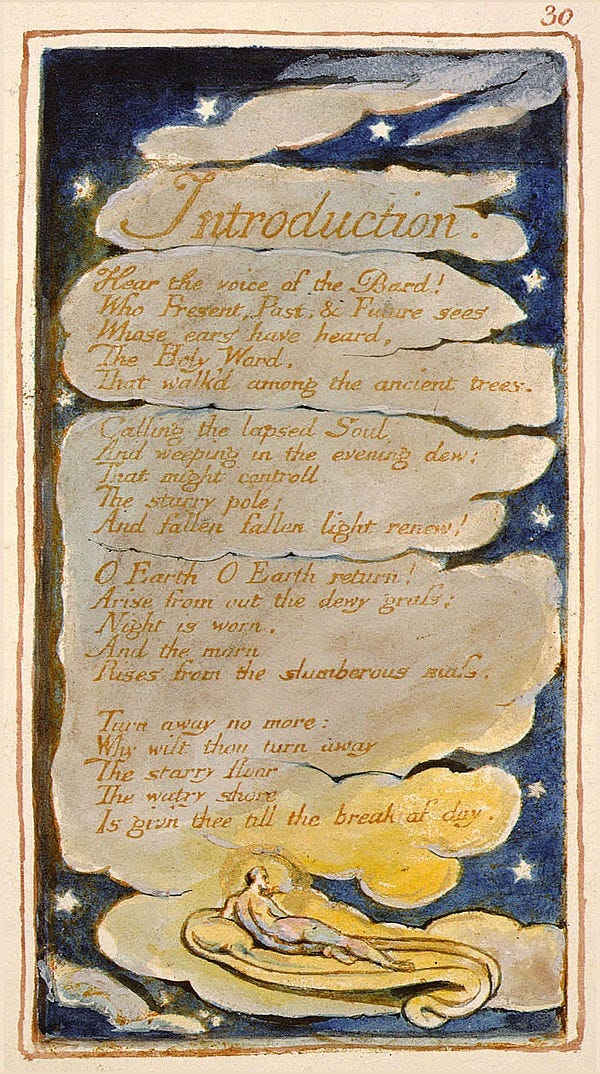

I was reading William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience, under the guidance of the brilliant Blakean Valentin Gerlier, when I began to feel very cold. Unearthly cold. In the poem, there was an image of Earth rising up from out of the dewy grass—which must mean… her own dewy grass? From inside of this impossibility, a polarity opened in the room and started to hum. Then, in the interval of this polarity, there emerged a magnetic field. And as I read on, or tried to, that magnetic field snatched me up and catapulted me to the dark side of the moon, where I found myself alone and freezing cold in the deepest of darknesses.

That moment forever changed my understanding of literature, language, and reading—which is quite something, considering that I was 38 years old, taking my third degree in literature, and had been working as an editor of literary fiction for 15 years. Reading had been the central activity of my life, and yet here I was, discovering I’d never had any idea what it could really do.

Ever since I blinked mid-stanza and found myself cold and alone in space, I have known in my bones that we as a society desperately need to re-learn how to read. That remembering how to read—how to really read—is one of the keys to the door of the next age. The age of revived imagination.

Though it took until I was 38 to grasp this, it’s kick-you-in-the-face clear when you take a moment to remember what I already knew as a writer: that poems and stories are alive. They’re not just adornment or entertainment or educational tools dreamed up in human heads. They are spirit emissaries sent Earthside and dressed in words in the changing room of the human imagination.

And if you meet a god, a spirit emissary from the otherworld, how should you greet them? Should you strap them to a table and start carving them up with a scalpel, to better understand what they’re made of? Absolutely not. Yet that’s what my decades of training in literary study had taught me to do, until Blake sent me to space.

So how else are we supposed to read? How do you read to greet the god in the text and let them work on you, and how and when did we forget this sacred magic? Let’s go.

***

“Of all things to be sought, the first is wisdom.” That’s the incipit—the opening—of the Didascalicon, a book composed in the 1130s by a canon and theologian known as Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalicon is the first book ever written on the art of reading, and here’s the first thing its author wants us to know: that reading is about attaining wisdom.

Not knowledge.

Wisdom.

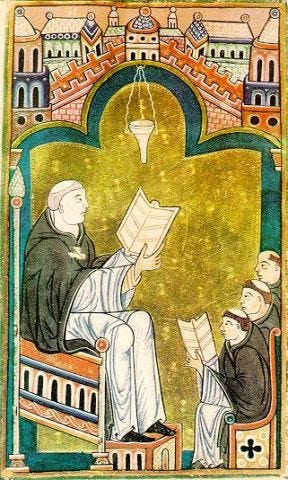

So how did Hugh and his contemporaries read for wisdom? Most notably, deep reading was a monastic practice. It was something devotees did aloud, in a group, not striving to absorb information and certainly not to be entertained, but rather in the hope of better knowing god. And since this was ultimately a mystic art, aimed at direct knowing of god, the essential preparation for monastic reading was to enter an attitude of deep humility. In his terrific book about all this, In the Vineyard of the Text, Ivan Illich writes, “Studies pursued in a twelfth-century cloister challenged the student’s heart and senses even more than his stamina and brains.”

But things were soon to change. Almost immediately after Hugh wrote the Didascalicon, the production of books altered radically. The alphabet itself changed; cursive script was rediscovered and introduced (because let’s not forget we’re pre-printing at this point; all manuscripts were handwritten); and new book-making materials and technologies emerged. The result? Reading changed too. Suddenly, books were things you could open and navigate from some given point in the middle, rather than having to read all the way through from the start. And, too, edited collections began to appear: volumes published on a single subject, so that by digesting the whole thing, a person could hope to emerge with a comprehensive knowledge of the field.

Not with wisdom.

With knowledge.

Before long, reading was something you did alone and in silence, instead of together and aloud. Illich writes: “After centuries of Christian reading, the page was suddenly transformed from a score for pious mumblers into an optically organized text for logical thinkers.” And this, Illich tells us, marked the dawn of scholastic reading, or bookishness—the mode of deep reading that would birth universities and academic study. The mode of reading that is, today, recognized as the exclusive way to engage seriously with a text.

I’m going to include Illich’s distinction between monastic and scholastic reading here, mostly because it’s simply such a delightful piece of writing:

The modern reader conceives of the page as a plate that inks the mind, and of the mind as a screen onto which the page is projected and from which, at a flip, it can fade. For the monastic reader, whom Hugh addresses, reading is a much less phantasmagoric and much more carnal activity: the reader understands the lines by moving to their beat, remembers them by recapturing their rhythm, and thinks of them in terms of putting them into his mouth and chewing.

Please know that I have put these words into my mouth and chewed them, and I highly recommend doing the same.

***

Of course, a lot has changed since the 1150s, not least the advent of first the printing press and then screens. And each of these changes has amplified and accelerated the core shift Illich charts in the twelfth century. Which is to say: deep reading has only become more cognitive, more solitary, more phantasmagoric, less carnal, and less inclined to begin with assuming a stance of deep humility.

But personally, I’d say there’s an even bigger problem with the way we learn to read deeply today, and it’s got nothing to do with the technology of the page. That problem is the Enlightenment, and the way its principles have leaked into all aspects of learning.

“Serious” reading today is framed as nothing so much as a scientific experiment. Whether it’s a book review or an academic paper, the literary scholar’s goal is invariably to excavate the text for the meaning hidden beneath its surface—to find, that is, the empirical “truth” of the thing. “We are neutral observers!,” goes the underlying logic. “We bring no subjectivity, no histories of heartbreak or particular propensity to be moved to tears by the image of a mountain or the wistful sadness of a near-rhyme. We are merely here to investigate until we can bring to light the objective truth of this object of study, be it gravity or a poem.”

And that, my friends, is simply not what a poem is. Not what a story is. We’ve got it all so wrong that it would be funny, if it didn’t matter so much.

***

(Does it, then? Matter so much? You might be thinking this is a pointless, niche ramble interesting only to over-schooled lit grads in black turtlenecks. I disagree. Well, of course I would. But here’s why: When we’re told that the only way to know the truth of a text is to bring the intellect to bear on it, it shuts whole hordes of people out of reading. People think reading is for brainboxes and that you need some extensive intellectual framework in order to enjoy a great book. This is dangerous, elitist bullshit of the highest order, and it has kept human culture’s deepest solace and joy and source of wisdom out of the reach of many people who have needed it badly, and could have understood it perfectly by simple dint of having hearts beating in their chests. Not to mention, it’s a grave insult to the gods in the books.)

***

So what to do? How do we learn to greet the god in the text again?

Back to Blake. Of course, being catapulted to the dark side of the moon might not sound like that much fun, and to be honest, it wasn’t. But it was a life-changing moment that gave me a bodily understanding of humanity’s wrong turns, and if that’s not divine intervention, I don’t know what is.

So how did it happen? That question is actually surprisingly simple to answer: through a less structured version of lectio divina. The Christians among you might already be familiar with this term, and might even have practiced it through a church group. But everywhere else, this practice has been all but forgotten—and I happen to believe it’s ripe for revival.

So what is lectio divina, and how is it done?

It’s a way of reading scripture (though I believe it can be used for any form of real literature, meaning any text that is home to a god) in order to come closer to god, by letting the words fully enter and inhabit you. It has five stages:

Preparation. Remember that for Hugh of St. Victor and his monastic mumblers, the first part of reading was entering an attitude of deep humility, so that the words and their wisdom could really reach them. It’s important to do something similar before embarking on your lectio divina—emptying yourself as much as possible of ego and any little demons of the day that might have their claws in your coat. You might set up a quiet, reflective space; sit in silence for a while; meditate; and/or say a little prayer, to the god of the poem in front of you, if not to any other god. Oh, and you’ll want to have selected your text. Since you’ll be going deep, try something short—no more than a couple of pages.

Lectio—or, reading, but likely not as you know it. Take a first, complete wander through the text, moving slowly and reading aloud if possible. Think of Hugh and his monks chewing the words like grapes. Here’s the key: do not analyze the text! Do not try to be clever. Simply allow it to enter you and flow through, like a river, until you’re attuned to its basic movement. Notice if any moments or images hit you with particular energy or clarity, but do not try to unpick them.

Meditatio. Now that you have a sense of the entire passage, go back to the start and read again, even more slowly this time. Whenever you reach a passage that feels particularly resonant, slow down. Stay with it. Keep reading the words, aloud if possible and with your entire imaginative capacity open. (For me, this means internally opening my spine in a way I can’t quite describe. I’m mentioning this in case it jogs anything for anyone, and in full awareness it probably won’t, and that is absolutely fine. I suppose what I mean to say is, be aware that your imaginative capacity probably doesn’t live in your head.) If you’re anything like me, there will be a temptation to start analyzing—to try to reverse-engineer the writer’s craft, mentally track the images and ideas to their source points, put little labels on passages to tell them what they mean, and so on. Do not do this! That’s like trying to solve a Zen koan with a calculator. Instead, hold your whole body open to the way the words hit it, and be curious about any sensations or images or movements that arise. Let the imaginal journey take you. If a magnetic field opens up, jump in (but be prepared it might not be fun).

Oratio, or prayer. In lectio divina proper, you’d now read the text a final time and let it move you into a prayer—some way to draw together what you’ve felt and learned and summarize it in a supplication or statement of intent. If you’re reading to encounter the gods of literature, I think you can be a little looser with this step. I like to read a final time and let the images wash over me until they find a sort of synthesis, a bodily sensation I can return to if I want to remember what I experienced and came to know in this session.

Contemplatio. Sit in silence. Not praying, not meditating, simply allowing the words to work on you. You’ll probably know when they’ve finished their work, but if not, ten minutes should do it.

If you do try this life-changing practice, please let me know how it goes, and whether you get catapulted to the dark side of the moon.

Love,

xx Ellie

Oh Ellie, this is just so wonderful and so timely. I have been engaging with Paul Kingsnorth's writing on the Abbey of Misrule in which he posits that the internet may be a portal, a way for dark forces to infiltrate our reality. And if this is true (and I am beginning to think that he is right) I think part of the way they may be able to do this is because of the nature of our bodily engagement with a glowing screen, it's ability to disrupt our natural hormonal cycles, the false light of back lit screens out of sync with seasonal rhymes.

And of course the speed at which memes become disseminated, out pacing our capacity to fully absorb their meaning and overwhelming our critical faculties, in Steve Bannon's phrase 'flooding the zone with shit'. (There is a whole other discussion to be had about whether the memes that flood the public consiousness via the internet are themselves the demonic energies that he's talking about, egregores)

So reading in the way you are describing is exactly the opposite of this, it is as a portal to opposite energies, ones of slow contemplative wisdom transmission at a pace that can be fully and deeply absorbed by the human mind. I am Irish and I always think of the stunning Book of Kells, the illuminated manuscript that must have had so much time and devotion dedicated to its creation, energy that comes through on its perusal. The Enlightment strip mined our perceptual awareness, imo, narrowing it to the decoding of glyphs on pages (and I also think the introduction of coffee had an influence on changing consiousness!).

Anyway, please, please keep writing and exploring. You are pushing the boundaries and we are all behind you!

As our society becomes more comfortable with psychedelic drug use, we will begin to see more metaphoric comparisons like this. I have been saying the same thing for years regarding music. As a sound healer (with over 10 years of experience btw, unlike so many sudden sound healers that sprang up during the lockdowns), I have always known about this. It wasn't until I began reading about psychedelic studies that I realized this is the language I needed to explain what sound, music, and the arts in general can do for the psyche.

The same can be said for dance, drawing/painting/sculture, the act of writing itself, as well as religious worship. Monks in the east have taught us to meditate using breath patterns, vocalizations, as well as what appears to be simple walking around the garden.

We have many opportunities for "psychedelic" experiences. I believe it is our birthright.

I love this perspective of reading as a psychedelic drug. I agree. I became hooked on it as soon as I was able to comprehend the act itself.