What does the fear of powerful women have to do with colonialism and hedgehog boxes?

Or: a story of English fear

Essentially, I am an absolute weirdo, perpetually trying to find my place in the world.

Seems like some of you can relate.

Having moved around an almost psychotic amount over the years, I’ve developed practices for quickly grasping a rough sense of what a culture is all about, and how I, an absolute weirdo, might fit into it—or not.

One of those practices is to visit bookshops. You can learn a whole lot about a place by studying what its publishers and booksellers are backing. And when I moved home to England two years ago after 11 years abroad, the lessons I learned in bookshops were illuminating—sort of stunning, in fact. They eventually helped me to grasp why I’d always felt like such a weirdo here, and beyond that, how and why this tiny little country might have come to play such an outsized and frequently damaging role in global affairs.

Everywhere I looked, there were books on etiquette in birdsong or how to befriend a vole or how trees are like vicars. I’m exaggerating, but only slightly. It was stunning just how many books I found in this category: the trad lettering or the swirling green leaves on their covers, the gentle prose and the vaguely defined notion of “nature”, all of them espousing some cosy, Radio 4 version of ecofriendliness.

England seemed to be trying to save the world, one hedgehog box at a time.

And if this all sounds terribly rude, know that I love this country, even though it frequently breaks my heart. That’s why I came back. That’s why I was in those bookshops, desperately trying to understand. And of course, there’s nothing inherently wrong with hedgehog boxes. They’re good! They’re good, helpful things. But the tone of it all felt so specific and so confusing. It struck me hard partly because of its stark contrast to what I’d found in the US over the previous decade. Of course, the US isn’t known for its environmental care. In the parts of the country I’d lived in, attitudes to nonhuman nature ran the gamut from outright hostility to (predominantly) blithe unconcern to passionate advocacy.

But rarely, in my experience, did those attitudes have encoded into them the weird, cosy condescension and paternalism that I was finding in England.

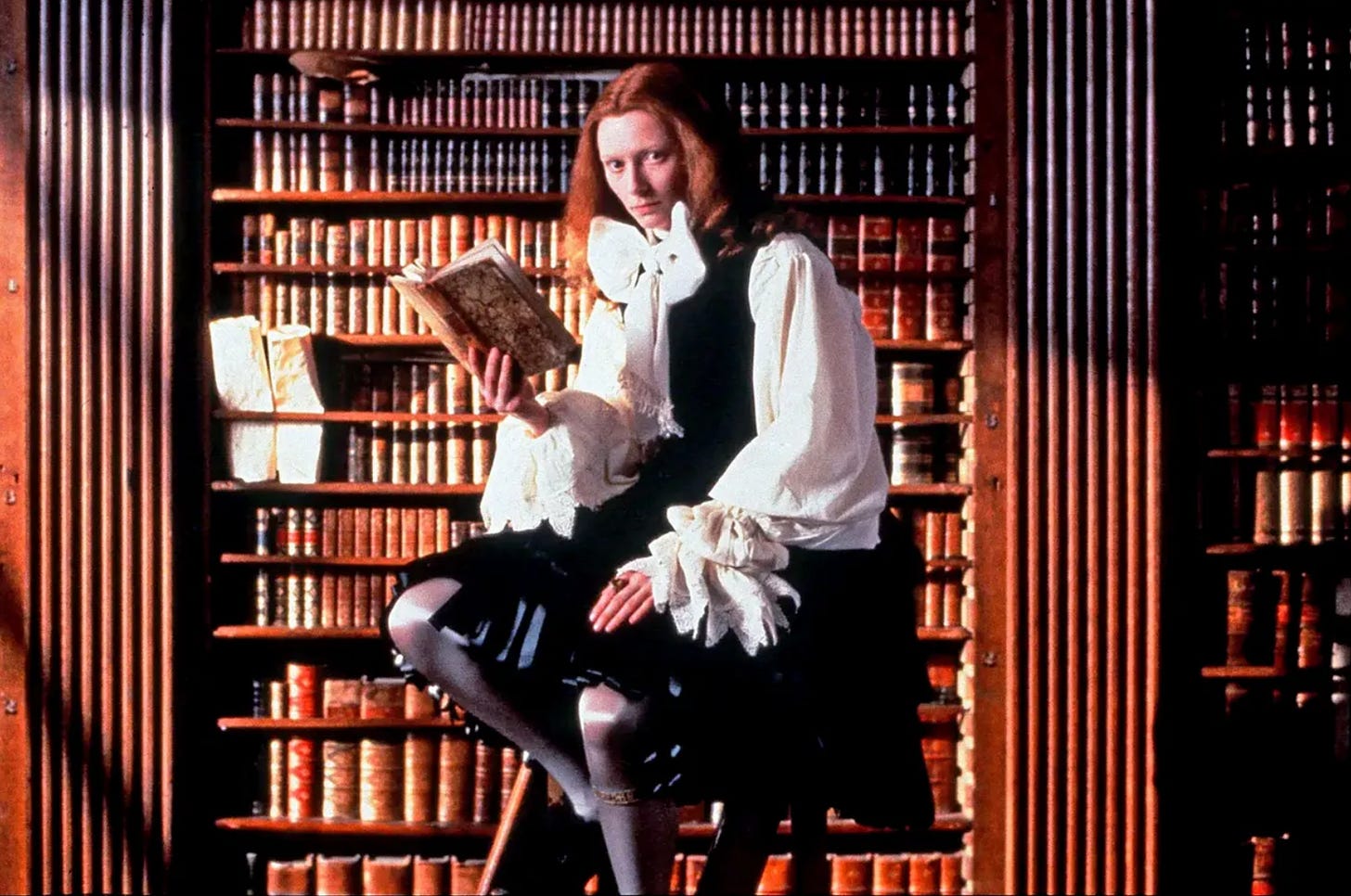

Virginia Woolf totally nailed this English attitude to the living world in Orlando. Orlando, already a woman by this point in the novel, finds herself in the mountains, several days’ ride outside of Istanbul (known to Woolf as Constantinople), with a “gipsy tribe.” I know that’s a deeply problematic term but I’m going to quote Woolf directly here. As Orlando gets to know this herding community, the differences between them come into focus:

Orlando had contracted in England some of the customs or diseases (whatever you choose to consider them) which cannot, it seems, be expelled. One evening, when they were all sitting round the camp fire and the sunset was blazing over the Thessalian hills, Orlando exclaimed:

“How good to eat!”

(The gipsies have no word for “beautiful.” This is the nearest.)

All the young men and women burst out laughing uproariously. The sky good to eat, indeed! The elders, however, who had seen more of foreigners than they had, became suspicious. They noticed that Orlando often sat for whole hours doing nothing whatever, except look here and then there; they would come upon her on some hilltop staring straight in front of her, no matter whether the goats were grazing or straying. They began to suspect that she had beliefs other than their own, and the older men and women thought it probable that she had fallen into the clutches of the vilest and cruellest among all the Gods, which is Nature. Nor were they far wrong. The English disease, a love of Nature, was inborn in her, and here, where Nature was so much larger and more powerful than in England, she fell into its hands as she had never done before.

Later, Orlando falls out with the leader of the herding community, Rustum el Sadi, after he finds her in tears one day.

Interpreting this to mean that her God [i.e., “Nature”] had punished her, he told her that he was not surprised. He showed her the fingers of his left hand, withered by the frost; he showed her his right foot, crushed where a rock had fallen. This, he said, was what her God did to men. When she said, “But so beautiful,” using the English word, he shook his head; and when she repeated it he was angry.

Orlando then throws herself into trying to decide whether “Nature” is indeed “cruel or beautiful”. Of course, it’s a meaningless binary, but the earnest way Orlando takes it up is one of the novel’s great comic turns.

And my god if this insistence on the benign beauty of nature isn’t the traditional English middle and upper classes in a nutshell.

The key, for me, is just this: that “Nature” in those Thessalian hills is “so much larger and more powerful than in England”. But of course, “Nature” in what is now England was once every bit as large and powerful as anywhere else. This island was once home to wolves and bears, to vast stretches of thick forest and fen, and long before that, to hippos, cave lions, and elephants.

The living world on these isles was so fearsome, indeed, that we killed it off, until we were left with a safe little island that harboured no deadly animals.

And only then, once we had thoroughly domesticated the living world; once we had made it unfrightening and therefore palatable to ourselves—only then were we able to “love” it, in this odd, cosy, condescending way that Woolf locates and lampoons at the heart of the national psyche.

This love, then, is in fact a form of control: I will curtail, cramp, and hobble you until you cannot hurt me, then I will claim and exalt this diminished version of you.

And there it is. The dynamic at the heart of so many abusive relationships—and not just romantic relationships but also a fearful culture’s relationships with the people and things it others and controls.

The former pupils of English boarding schools have long claimed that this is what they suffered: that their spirits were broken starting at the age of just six or seven, so that they could become, and be admired as, faithful proponents of empire.

It’s the dynamic I’ve seen so many women here, including myself, struggle against. Do you buckle to a conventional life that doesn’t feel right but which seems the only way to win social approval? Or do you accept the shaming, stigma, and othering that will come with following your instincts?

Of course, it’s a dynamic that members of minority cultures on this island are forced to confront every day. It’s also the dynamic the English played out in our colonies, where we worked to destroy all those parts of indigenous cultures that frightened us, so that we could steal the land, subjugate the people, take what wasn’t ours, and call ourselves benevolent bringers of progress.

This is how a history of ecocide and colonialism becomes chicken tikka masala as the national dish and hedgehog boxes for all.

And at the root of it all is fear. Fear of death, fear of hunger, fear or scarcity, fear of pain, fear of a world we cannot control.

I’ve come to believe that we English might have more than the usual quota of this fear. That it might be at the bedrock of the national psyche.

The good news is, fear is something you can work with. And once you’ve worked with it, you stand to be an awful lot happier and more free. In many ways, that’s the mission of this newsletter: to understand and remedy the ways mainstream English culture (and the WASPy cultures we’ve influenced) got trapped in the fear body and locked out of a more expansive, imaginative, generous way of living.

I’m going to be taking a deep dive into the origins of this fear over the next few weeks. Excitingly, that will involve, among other things, a conversation with Dr. Tim Flight, author of the brilliant Basilisks and Beowulf: Monsters in the Anglo-Saxon World. Stay tuned for that and more.

Love,

xx Ellie

I really relate to this Ellie, including your commentary on colonisation as a means of taming everything unfamiliar, different, ie scary.