Housekeeping: Last week, a brilliant group of geniuses staged a literary mind-rave/ritual/invocation of the great god Pan, just off London’s Fleet Street. I helped write the lecture, along with poet Thomas Sharp. If you want to read the script, you’ll find it linked on Thomas’s Substack, here.

Also! Now that I’m publishing these letters fortnightly instead of weekly, I’ll have time to make audio recordings of them. Hooray! So you’ll find one of those above. It’s the same as the essay, just said with my face words.

Hello, imaginauts,

And welcome to all the new subscribers.

This is a newsletter about imagination, the imaginal realm, the mystics who have excelled at voyaging to the imaginal, and the cultural lies and limitations that have left so many of the rest of us locked out of it—stranded somewhere apart from our imaginal home.

OK, but what does all of that actually mean?

Good question.

Since we’ve been joined by so many new readers lately, I thought it might help to go back to first principles. To try to articulate the fundaments of what I’ve learned and am learning about imagination, through many years of devotion. (“Try” being the operative word, since these topics slide out of language’s grasp like slippery fish.)

So here goes.

“Imaginal” does not mean “imaginary.”

This is the most crucial thing to grasp—everything else follows from this.

It’s a failure of the English language, really. It’s astonishing that Shakespeare’s own tongue gives us no effective way to separate the imaginary from the imaginal.

And yet we have to try, because if we don’t collectively rediscover the route to the imaginal realm, we are—to use the technical term—fucked.

It was Henry Corbin, a French scholar of Sufism, who introduced the term “imaginal” to the English language, in his 1964 essay “Mundus Imaginalis”. Corbin described the imaginal realm as “a precise order of reality corresponding to a precise mode of perception” (emphasis mine). This means that when we journey to the imaginal realm, that journey is absolutely not the same as taking a flight of fancy or getting lost in daydreams. It means changing our consciousness such that we can access a wholly different field of reality itself.

OK, but what exactly is that reality? Where does it live? How does it relate to our material world?

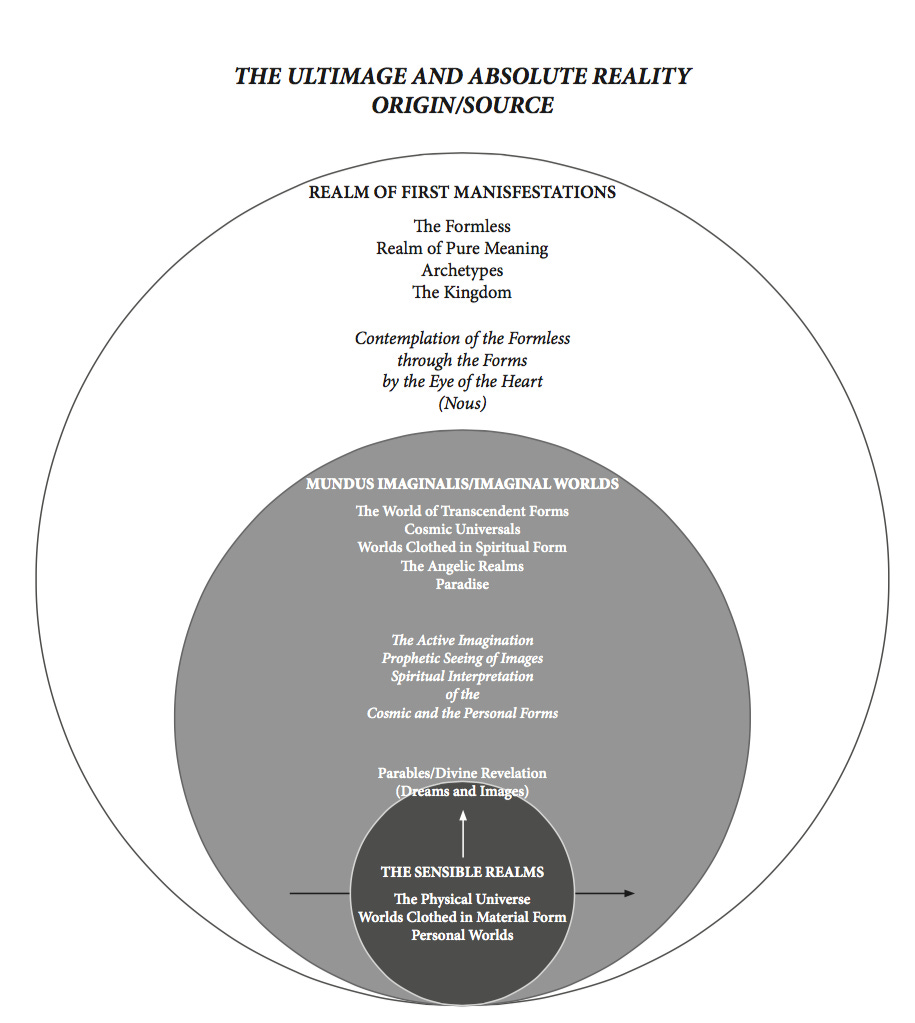

The most helpful answer I’ve found to these questions comes from the work of modern-day mystic Cynthia Bourgeault. Here’s her map of sorts to these interlocking realms:

Like Bourgeault, I experience the dimensions of reality as nested like Russian dolls, with the imaginal realm cradling our material world—in fact, giving birth to our material world. And the imaginal realm itself is cradled in an even larger and less determined divine consciousness.

In truth, the imaginal realm doesn’t just cradle our material reality. It’s not an inert layer sitting there like the custard in a metaphysical trifle. It is the active intermediary between the infinite and formless divine consciousness, and our world of IKEA and hot dogs. You might think of the imaginal realm as the dreamtime of that great formless consciousness—a place where stories and events are beginning to emerge, but like in a dream, their possibilities are endless because they don’t have to express themselves in flesh.

So is the imaginal realm a physical place we can go to? Like some kind of heaven that lives beyond the clouds? No! Bourgeault sums it up when she says: “These realms are ‘dimensions’ of an unbroken and seamless whole, not occupying an actual geophysical locus, but embedded holographically within the great abyss of consciousness itself.”

The imaginal realm is more real than the material world.

If there’s a founding belief of this Substack, it’s this.

Living as we do in the long shadow of the Enlightenment, we’re coming off several centuries of culture built around the core conviction that something is true only if it can be empirically measured and proven in a laboratory, by a man (always a man) in a white coat. We’ve had it drilled into us that we can trust only what we can detect with our five physical senses and our rational intellect.

That’s beginning to change now, and thank god. Because it would be weird, wouldn’t it? If the full truth of this universe coincided exactly with the human sensory capacity? Especially since we already know that some other living beings perceive colours, sounds, and smells that are undetectable to us. Demonstrably, there is more to this world than is demonstrable.

It would be very foolish to live in a world like this without a healthy dose of awe and humility. Without acknowledging that there is something very much bigger than human experience at play, and that our “reality” is likely only a very small sliver of the total, multidimensional reality that’s going down. Here’s Cynthia Bourgeault again, in her terrific book Eye of the Heart:

To our modern Western ears, the word imaginal may indeed seem to suggest some private or subjective inner landscape, “make believe” or fanciful by nature. But while it is typically associated with the world of dreams, visions, and prophecy, i.e., a more subtle form, the imaginal is always understood within traditional metaphysics to be objectively real and in fact comprising “an ontological reality entirely superior to that of mere possibility.” It designates a sphere that is not less real but more real than our so-called “objective reality” and whose generative energy can (and does) change the course of events in this world. Small though it may appear to be, it is mighty, as those who try to swim against it will readily attest.

Imaginal practice should not devalue but rather enrich and ensoul the material world.

We’ve all met those people who’ve taken one too many acid trips and are never coming back to earth. That is not what imaginal practice is about. I don’t despise material reality or want to escape it (not anymore, anyway). I love it. It is a tremendous privilege, to be bodied. This material realm—this place of, yes, IKEA and hot dogs but also grasshoppers and oak trees and jellyfish and mountains—this is the only place the great consciousness can feel itself. Can know all the joys and pains that come with having an edge and a life that must end in death, and loving others whose lives must also end in death. So we must take our living, our embodiment very seriously. Here’s a poem I love, which says this much better than I have here.

I’ve learned so much about attending to and loving the living, fleshy, green world from my brilliant teacher Alice Oswald. Alice’s poetic practice is rooted in an almost religious practice of noticing. She is fearsomely attentive to the living world around her, and to spend time with her is to be reminded that this, in fact, is our work, as living beings. I once heard her say that “matter is a courtesy”—and that is a thought to live by.

Every human has the capacity to journey to the imaginal realm.

If this all seems very niche—like the domain of someone who knits socks out of tofu or lives in a cave—think again. It is one of my deepest convictions that every single human has the capacity to experience the imaginal realm; that, in fact, this is part of what it means to be human.

The scholar of mysticism Evelyn Underhill heartily agreed, and wrote a book designed to help busy modern people access elevated dimensions of reality. Here’s one gem from that book, Practical Mysticism (which was written in the early twentieth century, so please excuse the gendered language):

The spiritual life is not a special career, involving abstraction from the world of things. It is a part of every man’s life; and until he has realised it he is not a complete human being, has not entered into possession of all his powers… [The mystical capacity] will teach [ordinary people] to see the world in a truer proportion, discerning eternal beauty beyond and beneath apparent ruthlessness.

While imaginal capacity is innate to you as a human, you can certainly enhance it, and this is precisely what Underhill aims to help you do in Practical Mysticism.

If you’re in any doubt that transcendent or imaginal experience is a universal human capacity, you might want to take a look at the work of archaeologist David Lewis-Williams. Beginning with the evidence of cave art and progressing through early temples, Lewis-Williams has argued very convincingly that the earliest artefacts of humanity—the first records we have of both art and worship—are artefacts of cultures that put altered consciousness and the attainment of ecstatic states at the very centre of their worship practices. Our oldest ancestors, he says, had essentially shamanistic cosmologies. They conceived of the world as comprising two realms—the material and the spiritual—separated by a boundary that could be crossed in altered states of consciousness.

And here’s the thing, the idea that always sends a shiver down my spine: Lewis-Williams has even argued that it’s this capacity for altered consciousness that critically differentiated Homo sapiens from the Neanderthals.

It’s hard to overstate the implications of this idea.

It means that imaginal capacity is not just universal and innate to humans, but is the very reason our species still exists. It’s the reason we survived. You might say, then, that it’s our purpose.

I have so much more to say, but I want to leave this letter here, before your eyes start to glaze over. Perhaps I’ll come back with a Part II next time. Either way, I’d love to hear what you make of all this, and where you’re at in your own explorations. Thank you for joining me on this journey.

Love,

xx Ellie

Thanks Ellie, this aligns so much with my own work around accessing the imaginal during solo time out in the out there. . Not that you'd know as I'm still getting ducks in line for a September launching. Alice Oswald was one of my intercessional figures, along with R S Thomas, in my MA a few years back. Total immersion. Brilliant! Looking forward to the next piece.

Yes! I'm totally with you on this...reinstating a poetic faith in the reality of the imaginal realm is a big part of my work. Nice to find your newsletter.