My friend's Self dissolved and stayed that way for two weeks. Here's our chat about it.

On living in a body while knowing that you're Nothing and Everything

Here’s a thing I’m very excited about: I’ll be speaking at Kairos in London on Thursday November 28th. There’ll be a talk from me, an open discussion, and a vegan dinner, all about the ideas that run through this Substack: imagination, the imaginal realm, mystical experiences, expanded realities, and Western culture’s severance from them. (Well, the vegan dinner probably won’t be about those things, but who knows?) If you’ve enjoyed my posts here, I think you’ll have fun, and most of all I would just bloody well love to meet you. Hope to see some of you there. Please invite your friends. Tickets at the link above.

For me, it was a moment on a beach in 2020.

A few weeks earlier, my life had dramatically exploded, pulverizing me in the process. So I went to the beach with a wise friend, and I cried and I prayed and my friend talked to me about the similar pains she had survived and about Aphrodite and about beauty and love, and I stood with my feet in the wide Pacific knowing for sure I would never recover, and then—something happened. I will never know what. All I know is that the world opened, revealing itself to be far larger and deeper than I had ever imagined, and it showed me colour for the first time, and showed me, too, a place, an expansive, whole, irreducible, infinite field inside me that I had never known was there but which had been fine all along. That day, I stepped into a different, brighter, more alive order of reality, of existence, and I have never been the same since.

This was my first personal inkling that our collective consciousness contract is shifting. That an expanded reality is tapping us on the shoulder, reminding us that it’s our true home. That moment has been the spur to all my work since, on consciousness, the imaginal realm, the nature of reality, and how imagination and ritual are the bridge between the realms.

I know that some of you are having mystical experiences like this too. And I know beyond doubt that these moments we’re gathering are part of a greater planetary shift in consciousness.

So when I heard that a friend had had his own mystical experience, and had written a book about it, I knew I had to speak to him about it and share his answers here.

Here’s what happened—or rather, what didn’t happen, as my friend would put it. Here’s the sequence of events in the material world that somehow split the veil and showed my friend that in fact, there was no such thing as an event in the material world, he was nobody, and nothing had been happening all along.

One morning, after a particularly vivid dream (he’ll say more about this below), my friend was struggling to work. He stepped away from his computer and into his garden—and soon, the world dissolved around him. “I stared down into the planting below me,” he writes.

A particular desert broom bush seemed to expand to fill my field of vision. A dense, almost impossibly complex tangle of branching green stems formed a net of shadow, through which little white butterflies and crane flies occasionally flitted, catching sunlight.

My body was abruptly filled with a deep stillness, as if my whole nervous system had suddenly relaxed, much more deeply than I was used to. I had a sense of dissolving, of spreading outwards. The boundaries not just of my body but of my selfhood seemed to be thinning out and then merging with the garden, and the leaf-shadowed morning.

No time. No boundaries in space.

All that was left was just Life.

It was seen very clearly that there was nothing and no one.

No one was here. Nothing was happening. […]

And it was seen that not only was there Nothing, but there had always been Nothing.

No one was ever here. Nothing had ever happened.

Just this: without time, without space, without end, and without beginning.

My experience on the beach was momentary: a few heartbeats that changed my life.

But my friend stayed in Nothingness for two weeks, and had to navigate family life, work commitments, and all the daily stuff of the material world, from a (non-)state of abiding nonduality.

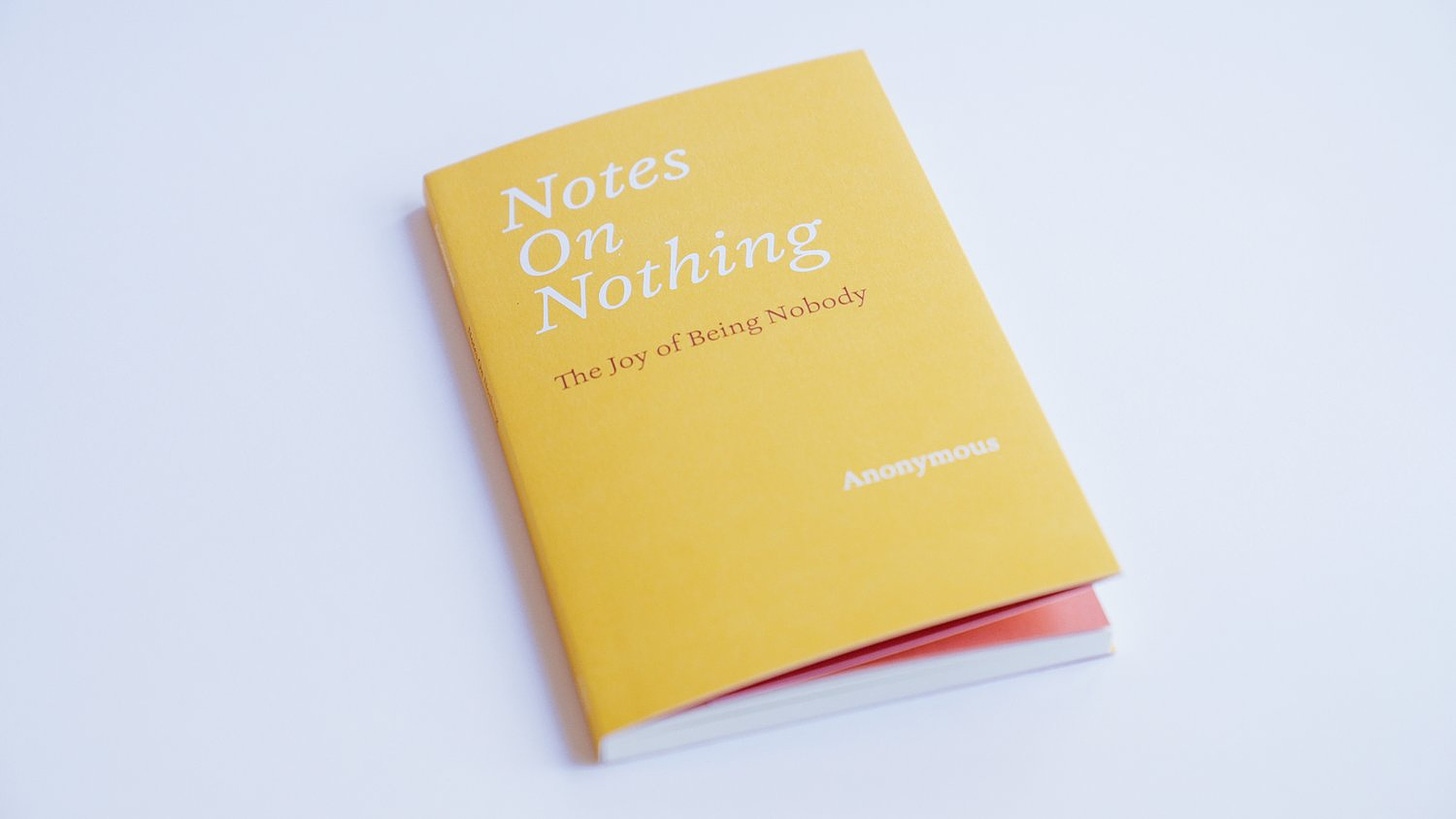

Notes on Nothing: The Joy of Being Nobody is a book about those two weeks. It’s published anonymously, because if those two weeks taught my friend anything, it’s that the story of whoever he is doesn’t matter at all. If you want to find out more about the book or buy a copy, you can do that here—but most of all, I hope you enjoy this conversation.

Before the interview proper, a little note for the writers among you: Notes on Nothing is published by a new, LA-based indie press, As Is Press. As Is is “committed to publishing beautiful, entertaining, and surprising work that explores themes of the numinous in the everyday, that gestures towards oneness and connection rather than separation, and that imagines new futures as we navigate the slow collapse of the present.” The press isn’t open to submissions from the general public, BUT the publisher is a dear friend and reader of this Substack, and he would welcome submissions from readers of this Substack in particular and only. If you have a manuscript that might fit the bill and which you’re looking to publish, drop him a line at: info@as-is-press.com. The publishing terms are: no advance, high royalties, author keeps the rights. Tell him I sent you!

Now, here’s what my anonymous friend would like you to know about Nothingness.

You say at the start of the book, “It’s not really clear to me what led to the two-week period of non-experience, in terms of causal events in time. There’s a story I can tell about it. But I honestly can’t say with any conviction or certainty that anything I ever did caused this non-experience to happen—or ‘not-happen.’” All the same, whatever that story is, of the events that might have precipitated such a shift—I would love to hear more about it.

Well—I am genuinely hesitant about going too far into some story about what led up to the so-called meeting with Nothingness I write about in the book. The reason for this is that our “egos”, let’s call them (or our senses of being separate from everything) constantly want to latch on to some process, or attainment, or secret, it seems to me. I’m cautious that someone might hear my particular story and think, “Ah—so that’s what I have to do!”

But the truth is, what we’re speaking of here is not an attainment at all. It’s just what is already always here. So no process or sequence of events can ever really “cause” or “lead up to” it. There’s absolutely nothing that can be done to “get” it, in that sense. It reminds me of that beautiful Rumi poem:

I have lived on the lip

of insanity, wanting to know reasons,

knocking on a door. It opens.

I’ve been knocking from the inside.

The “answer” has always been here—it is precisely un-caused.

I mention this in the book, too, but it’s also true that when there is no real sense of separation from anything, the whole idea of causation seems almost ridiculous, or at least gloriously moot. How could timelessness, wholeness, formlessness, have anything separate in it that could be caused by anything else?

OK—so that’s the (giant) caveat. It really hangs over this entire conversation I think.

So now we have another quandary. If I were to say a little more about what led up to the events of the book, the problem becomes—how far back do we go? I could tell you for example that a dream I refer to in the book, the dream I had the night before the so-called “meeting with Nothing”, was a very intense one. I dreamed that an unknown Indian ancestor from many generations back (my father is Indian), came to me, with an apology and a gift. I was suffused with white light for what seemed like hours by this figure. This dream did actually happen. Was there some “shift” in my nervous system after it? I genuinely have no idea.

If I were to go back years further, I might say that I am someone who has been curious about the nature of reality since I was a child. Someone who has always felt that there was some intuited aspect of things, some dimension, not acknowledged by what seemed to be the general consensus view of reality. I suppose I looked for it, this “dimension”. Was curious to understand it. I gravitated to art, film, literature, that pushes against the edges of consensus reality. Creating these kinds of stories became my life, personally and professionally. I also became interested in various religious or mystical traditions, including Advaita Vedanta, which was my father’s family lineage—though never as a particularly dedicated devotee to any of them. I meditated for a while. I explored my own personal psyche. I had various experiences, some immensely difficult, some transcendent. There was I suppose a certain “openness” in me.

But I want to end this answer by saying that I know for certain that there are people who have had deep and lasting mystical experiences—indeed people for whom there is no longer really any sense of separation, even—who never meditated a day in their lives. There are people with no interest whatsoever in these matters who were walking down the road one day and suddenly they were just—gone. I read a book quite recently called Collision With The Infinite by Suzanne Segal, which I thought was very interesting. She was a Midwestern woman who suddenly and spontaneously, while stepping onto a bus, lost her sense of being a separate individual. The experience caused a lot of suffering and upheaval in her life, and she was diagnosed with disorders by various psychiatrists trying to understand her condition. In the end she came to see her experience through a spiritual lens.

How do we speak of causation in such cases? It’s truly a mystery. Maybe that’s all we are left with, ultimately. How lovely!

I’m fascinated by the particular inflection of your experience; the fact that it was “nothing” that you entered. You’re careful to point out that you don't mean “Nothing” as in a void, but rather “Nothing” as in “No-thing,” as in formlessness. Can you say any more about what it felt like, physically or emotionally, to be in that place of No-thing? Were any of your senses particularly alive? Did the whole experience live in any particular part of your body?

Yes it’s an interesting question, why the “Nothing” formulation seemed like the “right” one to use. I do give “it” several other names in the book—I think my other favorite is probably simply Life. Just Life. Or maybe This.

I’m conscious that I’m really straining against the borders of language here, trying to speak about something completely ineffable—but it’s true that there was something palpable about the (non-)experience I’m talking about. Quite markedly so, in fact. A constant felt awareness of a sort of alive emptiness. A deep, deep sense that Everything really is absolutely Nothing.

Yes, you’re exactly right, it is really “No-thing”, rather than a lack of something. No-thing separate from any-thing else. Timeless, spaceless. Boundless. However, it’s true that there is somehow an illustrative quality to the word “Nothing”—it seems to point towards a felt experience, at least it does for me.

Maybe it’s something to do with the feeling that without any sense of being separate from anything, there just isn’t anything inherent in any particular thing—there literally can’t be. (I’ve discovered that the great Buddhist philosopher of nothing, Nagarjuna, is truly the king of speaking about this stuff. Eighteen-hundred years ago, he argued through rigorous logic that it is impossible to point to any inherent reality in anything. I only discovered him recently, I wish I’d known about him earlier!)

Another part of it is that it’s also a kind of simultaneous sensing—Nothingness is also absolutely Everything. It’s the whole, teeming, wild, untamed world at the same time. “Empty fullness” is a term sometimes used by the mystics to point towards this sense or feeling. Really, the whole thing is right there encapsulated in the second stanza of the Heart Sutra, one of the central texts in most schools of Buddhism: “Form is only emptiness/Emptiness only form.” That’s the total, wonderful paradox of it.

All this is beyond my ability to intellectualize it, of course. But it was somehow felt. There were sensations that came up in the body, sometimes intense ones. I speak about this in the book, but the main thing I would describe is a deep relaxation of the nervous system. It was like some default sense of tension was just not there for a few weeks. I think this is the basic tension of simply feeling like Something, like Someone. I think we always carry that default tension around with us, most of the time without even realizing it. At least that seems pretty evident to me now.

How did the experience of Nothingness affect your relationships?

Ah, that’s a question for my wife and family! Perhaps there has been a change. It’s genuinely hard for me to know. I would say that once again the sense of being a separate individual (we’ll call it the ego again) loves the idea that this is about making things better for itself. Better relationships, better experiences, nicer feelings and so on.

I just want to point towards the possibility that whether relationships are “bad” or “good”, it is all already boundlessness. Right here, right now, so to speak.

Did you form any sense of cosmology while you were in this state of nonbeing (or have you, since)? Do you have a picture of how Nothing relates to the everyday material world, spatially or causally? Did you have a sense of being held in any larger consciousness?

I think what we’re speaking about—Life—has no model. The so-called material world is also it. Everything is also it. And really, we could call it—This, Life, Nothing—anything we want. We could certainly call it “infinite consciousness”, if we wish.

In a sense what I’m trying to (impossibly!) point towards in the book is that every single model, every concept, every word about it instantly fails to touch it. How can the finger-tip touch itself? How can the eye see itself? OK, now I’m getting gnomic, but hopefully I’m gesturing towards what I mean.

I will share a couple of things. On the subject of consciousness—I am very interested in theories of consciousness, and at one point was quite immersed in the subject. I certainly would say that I like the model which suggests that consciousness is the ground of being, and that we as separate individuals, as well as our seemingly material world, are in fact just expressions of that consciousness. I can and will very happily expound on that idea, and argue the ways in which the rationalist, physicalist understanding of mind and world is deeply flawed.

But, somewhat unexpectedly, since the events I describe in the book, I’ve found myself using the word “consciousness” far less. For me, it just seems to carry too much baggage. It feels a bit too much like a model, a concept, to me. I don’t quite experience its “rightness” in the same way as perhaps I once did, at least when trying to speak about This. Now, of course all this may just be a particular preference of this particular person, and there’s one thing I can say for certain: my preference doesn’t really matter!

The phrase you use—“being held in a larger consciousness”—is one that strikes me now in a very nuanced and complex way, and points to something that has come up for me quite often since the events I write about in the book. On the one hand, my very direct sense is that there’s an inherent separation in that formulation—I do not feel that we are separate individuals who can be “held” in anything, ultimately. If we use “consciousness” as another word for what we’ve been speaking about here, then I do not feel there is ultimately anything other than consciousness.

But at the same time, it seems undeniable that we are gesturing towards something that feels far vaster than our little separate egos. And there is a sense to me that when our sense of separation dissolves, even for a short time, there is some ineffable feeling of Life expressing itself through us. As if things want to unfold in a certain way, and there is, at least, the possibility of meeting this with no resistance.

I can speak about this in relation to writing, and perhaps some of your readers will relate to this too. I think that when we are “in flow”, whether in our work or any other pursuit, what’s happening is that our sense of separation, of being an individual separate from Life, who has to own or claim Life, dissolves for a while. And all that is left is just what somehow wants to happen. I’ve certainly written things and had no idea where they came from, or how exactly they came to be. This book being a case in point!

So once again, we’re dancing with an absolute paradox here. Perhaps that’s all we can ever do.

You use the image of a whirlpool to describe the state of being. You write that though we all have this very clear sense that we are something or someone, our beingness is to the rest of life exactly what the water in a whirlpool is to the water in the rest of the river. I’m fascinated by this idea, perhaps because my own interest is in the imaginal realm, meaning the border dream between formlessness and something. Can you say anything more about your experience of these whirlpools?

Yes, the whirlpool is an image of our deep sense of being separate individuals. This deep sense seems to be a solid, boundaried thing, but in fact it’s made of the fabric of everything—it is everything; which is to say, Nothing! All there ever really was is the water, the flowing river.

It’s a beautiful image to me too, because it suggests that when we die, all that is really happening is that the whirlpool is dissolving back into what it already was to begin with… I think I actually first heard this image used by Rupert Spira, who is an interesting speaker on these things, though I use it in a slightly different way than him, perhaps.

Your work on the imaginal is incredibly resonant to me. I am someone who has ended up spending my whole life, to my mind at least, in service of the imaginal. I feel strongly that when I’m writing and creating, I am reaching into some place just as “real” as consensus reality, and trying to “bring down” or translate something from there. I’ve always felt this instinctively, since I was very young, and after being a professional writer for twenty-five years now, this process has become a very deliberate and customary part of how I go about my job.

As to how this “fits in”—again, I’m not sure how well models really work in the final reckoning. I like your description of it as the “border dream”. I think that one “upshot” of understanding things in this way, is that the world of form is free to become vastly wider and more subtle. To me, the imaginal realm is an extension or dimension of the world of form, a place just as real as the one in which we apparently walk around and have breakfast and feed the cat. In fact, it’s seriously real. If we’re not careful, the power and potency of that realm and its inhabitants can overwhelm us entirely!

Every artist struggles with this fact in one way or another I think.

Do you still feel that you are Nothing, even though you’re out of the direct knowing of the Nothingness? Or has your certainty of Something returned, now that you’re out of the experience?

This question hits on perhaps the only real “literary conceit” that I think I consciously use in the book, which is framing it as an event that had a beginning and a clear end. I speak in the book about the definite feeling, after two weeks or so, that Something—or Everything—“came back”. And it’s true, that feeling was there. The fundamental relaxation I spoke about earlier definitely went away. I felt more like “Me” again.

But in another way, nothing ever ended. And there have been more seeming experiences, or “non-experiences” perhaps, more aspects that have seemed to have come up since that time. Perhaps I’ll write about them one day, I’m not sure. Really, it doesn’t feel very important at the moment. I would say that what seems to still be here is just a kind of underlying knowing.

It’s perhaps the sense of simultaneity I mentioned. A deep acknowledgment that even as all the usual daily frustrations and reactivities and difficulties of life go on, just as they always have, they are somehow simultaneously also boundlessness. It’s something like: the background has come up closer, has merged more with the foreground. That’s the best I can do at speaking about it at this moment, it seems.

In fact, one thing I’ve noticed since writing the book is that my tendency has been more and more not to speak about any of it. To just remain silent about it. This isn’t coming from a sense of reticence or defeat or anything like that, it’s just a seemingly stronger and stronger acknowledgement that ultimately what is there really to say about it? Or perhaps more accurately what is there that can be said?

Although I seem to have attempted to say a few things here, so that’s something!

Though you are careful to point out that you don’t think that anything you did particularly caused this to happen, do you think there might be a “why” on the more cosmic level? Might there have been a reason for Nothing to have revealed itself in this way at this moment?

Yes, this question has come up for me a few times. I say more about this in the last chapters of the book; the society we have made for ourselves, especially these past few hundred years, is one which seems to massively reinforce our sense of separation. In a sense, the logic of the “ego” is the logic of our colonialist-capitalist society. It is the drive for more; more growth, more “progress”, more accumulation, more good experiences, and so on. This is a drive that can by definition never be satisfied, just as our sense of being separate must by definition always exist in an endless loop of wanting. Even when we achieve the thing that we thought would make us happy, we realize it hasn’t worked. So we go on to the next thing, and the next.

And now it (almost) goes without saying that this fundamental logic has led us into a state of global emergency. We may be on the brink of having to confront, without anywhere to turn, to hide, to run to, the global consequences of our own egos, of our senses of being separate from Life.

There are many accounts of this happening on a personal, individual scale—individual crises, or moments of intense dismantlement of the ego—leading to very deep shifts in how people understand themselves and their true nature. Might this be something that can happen, that wants to happen, on a much larger scale? It seems at least possible. It’s certainly interesting to ask what might happen if all our senses of separation dissolved at once. What might change in the world? What would happen to the drive for more? To what could it stick anymore?

Ultimately there’s no knowing. But it seems there are arguably more people interested in and exposed to these kind of messages than ever before. Including the wonderful people reading this Substack!

Are there any books or other resources you found particularly helpful while researching this book or trying to make sense of your experience? Anything you think readers of this Substack would love to read?

To be honest, I tried not to research this book at all! I tried to just report something, to evoke direct experience, to the best of my ability. I didn’t want to use any particular framework to speak about the events of the book and the seeming implications of them. I would hope that anyone can pick up the book and bring their own understanding to it.

But it’s definitely true that what came out seems to echo other accounts and other words used by people who have spoken about “Nothing” or these kinds of experiences.

The truth is this “way of seeing” is reflected and echoed through history, all over the place. Of course it is perhaps most prominently found in ancient Eastern philosophy, in the Upanishads, in the Vedic corpus, in the Tao Te Ching, in the Buddhist texts, in the Sufi tradition. It’s echoed in the Kabbalah. But it’s certainly in the West, too, in some of the gnostic traditions, in Christian mysticism, Meister Eckhart and so on. Some have found traces of it in the Bible. But really it’s everywhere, it’s speaking to us. In songs, in poems, in art. In the world. It’s with us all the time. It is the ultimate secret, as the Sufis say, because it’s hidden everywhere.

In terms of contemporary Western writers and speakers, people like Rupert Spira or the philosopher and scientist Bernardo Kastrup perhaps speak about it from one particular angle. People like Tony Parsons speak about it, somewhat provocatively, from another angle almost entirely. I mention some others in the Acknowledgements section at the end of the book. Some of them have YouTube presences that will no doubt lead you down wormholes if you feel like jumping into them.

William Blake takes me there, I know you’ve written about him before; Rumi takes me there (without a doubt in my mind, they knew…). But I think the ultimate authority on this is ourselves, is our own direct introspection. As the saying goes, if you meet Buddha on the path, kill him.

Did your experience of Nothing give you any insights on how to navigate material reality, with all its pains?

Sometimes when people hear about the kind of view I try to evoke in the book, I think they might equate it with a kind of nihilism. I think what can sometimes happen—and this is perfectly natural for the ego, for the sense of separation, to do—is that the person instantly turns Nothing, or Life, or This, into a concept or position it can hold. The person hears “Everything is Nothing” and thinks this means that what is being said is that, for example, pain and suffering is “just an illusion” and should be ignored or simply accepted, or something like that.

This is a serious misunderstanding. Because it is to take Nothing as being for someone—as being an idea that someone can claim as their own and use as a prescription. There’s no negation here of pain and suffering. No suggestion that it “isn’t real” for people or should just be "accepted”. Pain and suffering happen. The work to mitigate pain and suffering happens. I am the child of political activists and have many strong opinions on how pain and suffering in our societies can and should be ameliorated. I suppose all this view is really suggesting is that pain and suffering is also boundlessness, arising as pain and suffering.

As I mentioned before, it’s always very striking to me that it seems to often actually be suffering—and often immense, unthinkable suffering—which seems to be a doorway for people into this kind understanding of reality. And it is no coincidence I think that most of the traditions which see things in this way, and have done for thousands of years, stress the importance of spreading love and kindness and giving aid in the world of form.

So among everything else this is a call for love and kindness. For giving aid. For dancing with the paradox, the mystery, as best we possibly can.

Wonderful conversation and the book intrigues me as well as Suzanne Segal's book which was mentioned. Thank you for conducting and sharing this interview. I noticed you asked the anonymous author if he read about others' experiences to help make sense of his own. It brought to mind, Jan Frazier's book When Fear Falls Away, an account of a sudden awakening. She is/was a creative writing teacher and writer. After her sudden shift she found resonance and recognition in reading about the experiences of others' enlightenment that helped her integrate what was happening. I love that cat vomit makes an appearance in her book. She has written others too. I thought you and your readers might enjoy her books.

It is hard to find words to describe the state of formlessness, the place where I dissolves into all, where our individual boundaries merge into the pulsation of existence, of Life, of This. Mystics throughout history have attempted it,some, like Blake, Rumi, Hafiz and the great beings who have graced our planet and illumined the path for others, manage to convey the experience through their words, images or presence. I thank you, Ellie and your nameless friend, for this clear, humble and true account of touching the space where all becomes one. I too have touched that space, and just knowing it is there, and catching glimpses through meditation, nature, music and silence fills my life with wonder and joy. The way home indeed. I love that you are exploring this topic from so many different view points.

And wouldn’t it be a wonderful world if everybody touched this reality at least once in their lives, and love and kindness, tolerance and awe-inspired humility became the norm for us humans.