Hi! If you know someone who’d like to read about the imaginal realm, this would be a great letter to forward to them. It’s the first of three I’ll write introducing that realm.

Someone once told me that my voice was the exact pitch of room noise, making me impossible to hear.

This is probably true, but not a great chat-up line.

And what this huh-that’s-a-strange-thing-to-say-to-a-person comment hides is that in fact, no human voice is ideally pitched to be heard by human ears.

Because our ears didn’t develop to hear human speech. Most human speech actually falls well below their peak auditory range.

What the hell? Is this a species-wide design flaw?

No. Our ears are just perfectly calibrated to hear something else.

What?

Birdsong.

Here’s acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton on On Being a couple of years ago:

We have a very discrete bandwidth of super-sensitive hearing. And that’s between 2.5 and 5 kilohertz, in the resonant frequencies of the auditory canal.

Is there something in our ancestors’ environment that matches our peak hearing human sensitivity? Because most of what I’m saying right now, except for the “s” sounds and the high-pitched sounds, falls well below that range. And indeed, there’s a perfect match: birdsong. Birdsong. [laughs]

Why would it have any benefit to our ancestors to be able to hear faint birdsong? Why would our ears possibly have evolved so that we could walk in the direction of faint birdsong? Birdsong is the primary indicator of habitats prosperous to humans. Isn’t that amazing?

Yes! It is amazing. And not just because it reveals so much about how our oldest ancestors navigated the world.

But also because it tells us that those ancestors were once fluent in a language we’ve lost, and that they were fluent in this language for so long that it is hardwired into our bodies.

It tells us that human speech—an incredibly recent, almost newborn technology designed to carry meaning between the cognitions of supposedly discrete humans—is only a very thin slice of the communication that’s going on at all times.

It tells us that we move through layers of meaning many orders of magnitude larger than we allow ourselves to believe in or experience, and that this is not some spiritual claptrap but hard biological fact, for those who privilege such things. The evidence is right there, on both sides of your head.

But why am I talking about all this in a letter about the imagination and the imaginal realm?

Because our cultural understanding of imagination is so wildly impoverished, and because birdsong offers a key to a deeper, truer understanding of it.

We’ve come to understand “imagination” as a private capacity—a commodity, even—that we carry inside ourselves in little personal portions, and can use to envision ideal futures, manifest our dreams, pick colour schemes, write screenplays, or—the most formidable imaginative task of all—figure out what’s for dinner every goddamn day of the never-ending week.

This is a little like thinking that birdsong is your own personal capacity to imitate an owl.

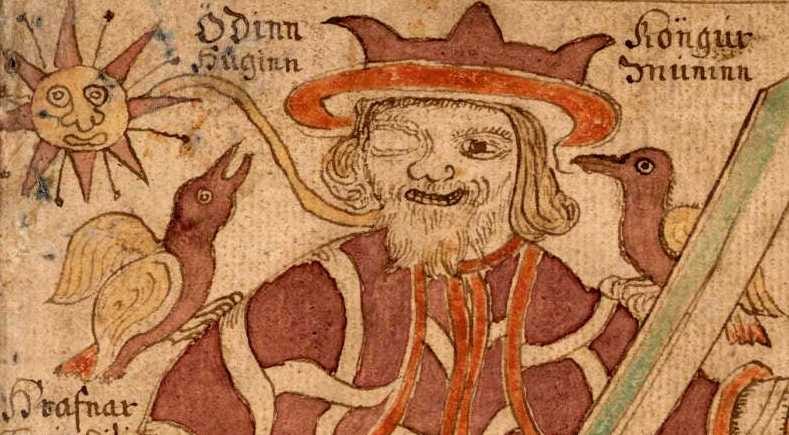

Like all languages, birdsong has its own grammar. It isn’t a series of notes sung at random; it’s music that stitches the world together in coherent, beautiful patterns that most of us just happen not to be able to understand any longer. (Though this wasn’t always the case: check out the language of the birds, the language postulated in some medieval and occult belief systems, through which birds were said to communicate with the initiated.)

And though most of us don’t understand or recognize birdsong these days, our bodies were made to understand and receive it. The capacity is latent in all of us, and it doesn’t live in our brains but in our dormant sensory organs.

The imaginal realm is just like birdsong.

Just like birdsong, it’s all around us, singing to us. It is a field of harmony and potential. It has its own grammar, its own laws of possibility, its own pitch. Cynthia Bourgeault describes it beautifully, in Eye of the Heart:

When all the intellectual abstractions have been stripped away, and it is allowed to speak in its own native tongue, what it speaks of, with surprising simplicity and directness, is beauty, hope, and a mysteriously deeper order of coherence and aliveness flowing through this earthly terrain, connecting it to the infinite wellsprings of cosmic creativity and abundance.

If there’s anything like a personal imaginative capacity, it’s not skill in sitting at a desk and coming up with stories, or putting paint on a canvas (which in isolation are to true imagination what trotting out an owl impersonation is to hearing birdsong).

No: it’s skill in attuning to this beautiful, hopeful, and mysteriously deep order of coherence and aliveness. An order that, like birdsong, is already right there. We don’t have to dream it up. We just have to learn to listen. To hear it. And that doesn’t start in our heads, but in our senses.

Next week, I’ll write about how and why we can uses our senses to enter the imaginal.

Love,

xx Ellie

Bang on again. The shift from the feelings to the mental capacity was, I believe, a plot to enslave us into becoming units of production in this economic nightmare. The capacity of the brain to produce neuronets in the unconscious enabling quick access to skills, has been used to brainwash us with programmers designed to make us adhere to what we are told rather than what we sense and feel. Listening to these programmers ensure we live as others want. Our feeling nature is the only thing that is uniquely us. We can trust it implicitly because it's dedicated to our survival. As all other animals know. In trusting them, we open up to the Greater Consciousness beyond what we are told.I think this is what our imagination is in part. Looking forward to your next take on all this. You are a treasure.